In Namsa Leuba’s photographs, one enters a realm of bold colors, striking forms and sometimes-otherworldly figures. Whether these contexts are clearly constructed or more organically situated in space, Leuba positions her subjects in ways that draw attention to the historical narratives through which Western aesthetics and social expectations have perceived and understood African bodies. Adopting and reframing conventions of photographic ethnographies alongside visual tropes of European fashion, her images push the viewer to confront one’s own ideas of what is sacred, valued, or celebrated. These images are striking and rigorously assembled, yet the influences from which they are constructed remain clearly legible. Through Leuba’s eyes, these symbols speak differently.

In the weeks following the October 2015 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London, Namsa Leuba spoke about how she works with visual icons in order to deconstruct and reconceptualize prevailing ideas of self, history and context.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo: 2015 has been a very busy year for you—just coming off showing at 1:54, but also with your work featured in exhibitions at Art Twenty One, the Saatchi gallery, Photo Quai, and in “Making Africa: A Continent of Design” at the Guggenheim Bilbao. How do you deal with the ways in which your work has been exhibited, and continues to be circulated?

Namsa Leuba: Yes, it’s been an extremely busy period. For a few months I was in Lagos, and I just came back from Tokyo, where I did a workshop, participating in the Tokyo International Photo Festival. I think at this stage in my career, everything seems to make sense. My work centers on these ideas of looking at the African continent through Western eyes, and being very conscious of all the implications and structures embedded in that process. It’s been really impactful to interact with people who are perceiving these works, people who are ‘mixed’ or black African individuals who have lived abroad, and seeing how they respond to these images, how they relate and find this strategy very relevant to their particular emotional or creative contexts. It’s really touching.

Tell me about Cocktail, African Queens, and Zulu Kids—the three series that you showed at 1:54 with Art Twenty One. Even though they employ such different compositional approaches to pose and subjectivity, there is definitely a conceptual line one could draw from one body of work into another. What were the thought processes that led up to creating these series?

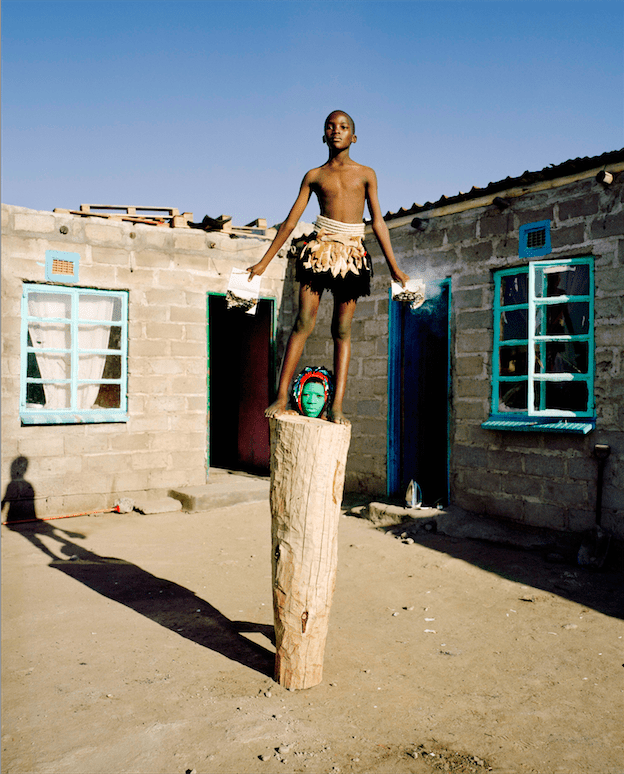

Absolutely, I think that continuity can be traced back to my first series, Ya Kala Ben. Zulu Kids is an extension of that project—and while Cocktails and African Queens are not, there’s still the idea of recontextualizing African elements through my camera that remains. For all of these series, I select the elements meticulously for the function of the picture, with everything in its place. Through this reconceptualization, I bring the subject matter into a framework traditionally considered for Occidental tastes and aesthetic choices, but simultaneously I try to bring a combination of acidity and freshness into the mix. For my more fashion-oriented projects, like Cocktails and African Queens, I was inspired by the strength and potential of African women to be prophets and warriors. But also, in the ways that I place their figures in the frame, there are echoes back to Ya Kala Ben, where the individual stands as a statuette.

With Ya Kala Ben, I set out to reconnect with the Animist practices of my Guinean side, my mother’s side of my family. It was with this project that I started really to work on African identity through the Western eyes. Working from the iconic poses of sculptures in West African cosmogony, I arrived at the statuette as a compelling visual tool to understand various practices of ceremonies and rituals. For me, it was interesting to use to the human form as an embodied way to explore the significance of these statuettes. Human beings need not be animated, they are alive—living and breathing figures. This concept of embodying statuettes triggered really violent reactions during my time in Conakry. Many serious traditionalists thought it was sacrilege, because I decontextualized parts of religious practice. But I deconstruct the body in order to reconstruct the gaze, to put something sacred into another context to see how that shifts interpretations.

So you’re creating these different frames with which one can view visual idioms often seen in sensitive contexts. How did that premise operate within the context of Zulu Kids?

That project harnessed ideas of cultural syncretism, but not through the symbols of the statuette or the mask, which I used in Guinea. In South Africa and Lesotho I focused on the energy of the youth, and in feeding off their poses, opened up ideas about how gesture could provide markers through which to reflect on history, but also what is to come—after all these kids hold the future of the nation. In Zulu Kids, you can see a lot of antiapartheid movement gestures. It conveys a great deal of power, seeing these young people, elevated off the ground—raising the Amandla fist, burning ethnic passbooks in their hands.

Considering the multiple historical, visual and cultural references embedded in your work, I’m interested in how you seem to look at categories and frameworks less as guidelines or boundaries, but more so as things that you need to destabilize, jump over, mix in-between. Even when considering a body of work like Ya Kala Ben, you’ve described it as fieldwork, almost as if it’s ethnography of your own history. Then on the other side, you have series like African Queens and Cocktail, where you’re dealing deeply with ideas of cultural aesthetics and subjectivity mediated through the fashion lens. How did these sensibilities develop?

I was born in Switzerland, and grew up there—I had a Swiss education. So a lot of my visual sensibilities, my interest in fashion, that comes from growing up here. Even in a project like Ya Kala Ben, where I’m delving into the histories and cultural elements of my Guinean background, I think you can perceive elements of European aesthetics. I mix all of these references and categories because I am a mix of all of these things. I really assess and convey what I want, and that is based on whether it’s interesting, compelling to me. In the process of realizing these projects, I acknowledge that parts of my identity are in permanent struggle. There is always the possibility to try and reconcile them—but I don’t try to. I play with ideas of cultural syncretism, but I don’t try to reconcile Guinea and Switzerland. I acknowledge and explore both sides, fully.

How do you think those tensions play out in how you deal with the human figure in your work? There are these histories of West African sculptural iconography you’re dealing with, but also European conventions of fashion posing that show up. How do you frame these ideas of identity within compositions that are openly constructed and rather meticulously arranged?

Often, when I’m working on these projects, I build a relationship with the photographic subject prior to the shoot, so they have a sense of where I’m coming from. I also do a lot of location scouting at the same time—a small moment in the middle of a market or something can be immensely impactful to the process. Because I know that for me, a single image can take three to four hours to be fully realized, and that the subject matter that I work with sometimes is very sensitive, I also complete many preparatory sketches. In working with the tensions between more Western or African visual cues, that you see through the colors I use. While the more fashion-oriented series are very worked and set within a studio, the bright colors tell more about the Western gaze or expectations of the African figure than the actual figure. With series like Ya Kala Ben or Zulu Kids, there is a freshness of color, but not as flashy—I work only with natural light there, so there is no sense of modification or enhancement.

There is a beautiful set of images in Ya Kala Ben where you photograph a group of acrobats. The interlocking of powerful limbs, enmeshed bodies, it’s so arresting—especially because you treat them so delicately. This series struck me specifically, because many of your other photographs establish a critical distance between you and the subject. You give them their own room to occupy the space, interact or stand apart from the conceptual and physical environment. Yet with these acrobats you get up close. How did that come about?

For the acrobats, you know it was something special and different. Rather than a meticulously planned session, it was so free flowing and fluid—really focusing on the physical construction of the body, while the rest of the series concentrated on the sociocultural constructions of figures. With these physical artists, I wanted to show their flexibility, their strength, and to go close up seemed the only way to do that justice. I wanted to show all the complications of the body, all the possibilities of the human form—the human identity.

Namsa Leuba is a photographer currently based in Lausanne, Switzerland. She exhibited at the third edition of 1:54 Contemporary Art Fair in London with Art Twenty One (Oct 2015). She holds a BA in Photography and an MA in art direction from ECAL/University of Art and Design in Lausanne, Switzerland. In 2013, she was one of the winners of the Magenta Foundation’s prize for emerging photographers, and in 2012 she was awarded the PhotoGlobal Prize at the Fashion and Photography Festival in Hyères. Her work has been featured in exhibitions at Quai Branly Museum, France (2015); Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain (2015); Daegu Photo Biennale, South Korea (2014).

Oluremi C. Onabanjo is assistant curator and artist liaison at the Walther Collection. She holds an undergraduate degree in African Studies from Columbia University, and is pursuing a Master’s degree in Visual, Material and Museum Anthropology at Oxford University. She has assisted with exhibitions at the Museum of African Design, Johannesburg; No Longer Empty, New York; The Walther Collection, New York and Neu-Ulm, Germany; and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.