As the wave of interest in African Art continues, the second edition of 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair runs alongside a host of other events which dominate London’s October art scene. From 16–19 October, 1:54 showcases 27 international galleries, 11 from Africa, at Somerset House. Over the past few years, the market for African Art has steadily grown and been nurtured by the introduction of art fairs, exhibitions, and international galleries/museums geared towards both traditional and Contemporary African Art. 1:54’s purpose as a platform for galleries, artists, and curators to promote the reception of African Art as a global interest is just one articulation of its current excitement.

Over the next few days, we will be posting a series of interviews with three of this year’s exhibiting galleries, conducted by Emma Wingfield, a freelance art researcher and writer, with a background in African Art based in NYC. The interviews aim to discuss the galleries themselves, their views on their local and global Contemporary African Art markets, and their artists/involvement with 1:54.

First up we have Ashleigh McLean, Gallery Curator WHATIFTHEWORLD in Cape Town, South Africa.

Whatiftheworld gallery started at a time when very few galleries were looking at artists just finishing their studies at universities and/or self taught. Although hardly an issue which solely plagues Contemporary African Art, it is nonetheless a serious issue. As the gap widened between these artists and what much of the global art market would term established/recognized artists within a South African context, the need for a new platform grew. Ashleigh McLean began her curatorial career by staging installations and interactive art pieces as part of small scale urban interventions. She optimized this demographic of artist looking for exhibition space. She studied formally at the University of Cape town and following graduation began creating her own shows, in pop up spaces, in an attempt to create an ideal exhibition environment for herself, the people she graduated with, and others in a similar state of limbo. Although McLean no longer creates her own art, she still very much views her work at Whatiftheworld as art. Many galleries schedule shows and leave the details to the artist to create with very little support. McLean and Whatiftheworld “work closely with their artists whenever possible”, creating exchange, as the exhibition develops. For an artist, working in a studio can be isolating. Whatiftheworld offers a solid foundation and sounding board.

Whatiftheworld was founded in 2008 in Woodstock, South Africa. Sitting on the outskirts of Cape Town, Whatiftheworld’s location easily leans itself to the promotion of South African artists who have been underpinned by overarching global contemporary art movements. The gallery’s goal was to take younger artists from South Africa, who were just starting out and create a professional gallery environment to present their work. The gallery would not only offer a physical space to exhibit, but would also nurture and provide the valuable infrastructure to support artistic professional development. Whatiftheworld, a completely self-funded independent body, can provide a platform for the appreciation of multi-disciplinary aesthetics and a creative environment for those artists thrive in. They were also able to focus on the art they found engaging, by balancing easily sellable items such as drawings and paintings, with things not necessarily seen as massive money makers (performance and urban engagement type projects). This multi-disciplinary approach is emphasized in their choice of gallery name. Whatiftheworld was inspired by the many projects going on in the gallery space. Playful, yet serious, it is a proposition that is heavily utilized within the gallery context.

Whatiftheworld is located in the predominantly immigrant community of Woodstock, in a synagogue that was decommissioned in 1980 following the departure of the Jewish community. Today, the primarily Muslim area hosts a plethora of arts studios, independent young businesses, designers, and light industry. Woodstock was passed over by the Group Areas Act during apartheid, and has therefore retained its raw, gritty character. Now considered a local art hub, Whatiftheworld was the first gallery to move into the area. Its location creates an interesting social crossover between the local community and the gallery’s clientele. The gallery brings in people/collectors who would not necessarily frequent this area. While no one living in Woodstock is currently buying art, they are interacting with it, a connection Whatiftheworld continues to cultivate. According to McLean, this is indicative of South African society. The very rich and very poor living side by side, brushing up against one another. She states, “In today’s secular society, art galleries have become the “new” religious space”, a mutual place of worship by anyone from any background.

The huge increase in interest in Contemporary African Art, according to McLean is not something temporary, like the bubble within Asian Art. It continues to sustain interest due to its integrative processes. It is not just an exotic interest. McLean argues that public exhibitions have been vital in exposing the work to and gaining interest from the international art community. She said that public exhibitions have proved to be great opportunities to create collaborative relationships with other galleries, exposing their artists to new communities and building extensive art networks. McLean also argues that Biennales are also incredibly important, having the ability to shift career paths of individual artists. These exhibitions show African Art for what it is and help to educate people on how to talk about the art. For McLean, performance art has been hugely important in nurturing the recognition of African Art. It is interesting and engaging, which only further identifies African Art as not only high quality in physical appearance, but strongly representative of complex ideas.

The local art market in South Africa is rapidly growing, and has spread to other countries on the Continent. More and more galleries are turning up in South Africa, Nigeria, and Ghana. Formal art institutions are also being established for teaching art making, encouraging intellectual critical thinking, and engagement with art. African collectors from the continent are also starting to buy more and more art. As this continues to grow, so will the Contemporary African Art market.

Next year, South Africa will be getting its first Contemporary Art museum in the form of a science museum in Cape Town. McLean argues that this will dramatically shift reception of African Art in its local context. It will change the amount of people traveling to South Africa specifically for art. It will change the way artists work; the idea of producing work for museum scale spaces is very different from working within a more domestic environment created in a gallery context. Museums are spaces for critical dialogue and trans-national conversations. McLean argues that there is so much more to come out of Africa. African art is stronger because the environment it is produced in can be less structured or compartmentalized by controlled institutions.

The collecting scene in South Africa is small, but strong. McLean estimates around 30-45 serious collectors living in South Africa who are regularly buying Contemporary African Art. The gallery tries to break through the conservative outlook which plagues many South African buyers. At auction, there is no shortage of people willing to spend exorbitant amounts of money on master painters from South Africa. McLean states that the contemporary art market is not there yet, but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t gaining traction. This is why art fairs like 1:54 are so important. As a younger gallery, working towards creating and cultivating a younger generation of collectors, these public and international art fairs offer opportunity to cultivate such relationships. McLean estimates around 60% of their business comes from the US and Europe. Developing their international Contemporary African Art collectors is just as important as developing the local.

This is Whatiftheworld’s first year exhibiting at 1:54. McLean and the Whatiftheworld gallery were eager to see how the first edition of 1:54 panned out. The art market is highly competitive and participating in international art fairs is a huge financial commitment. However, as McLean states, 1:54 is unique in that it not only presents a stage for Contemporary African Art unlike anywhere else in the world, but it also caught the attention of collectors who fly to London specifically for the fair. The fair is not without criticisms, principally concerning the ghettoization of contemporary African Art away from the rest of the contemporary art genre. Having a fair solely dedicated to “African Art” stimulates judgement regarding the art form as outside the mainstream contemporary art market. The question then is, when will African Art become just part of “Contemporary Art”? On the other hand, as McLean is quick to point out, this is also one of the fair’s strengths. Having a focus based art fair is extremely useful and will encourage the exhibition of the best of Contemporary African Art right now. It has an opportunity to cater to a particular niche interest, much better than a larger “contemporary art fair” could. 1:54 provides a necessary catchment area, displaying African Art as Contemporary Art, and for any collector with a specific interest it is perfect.

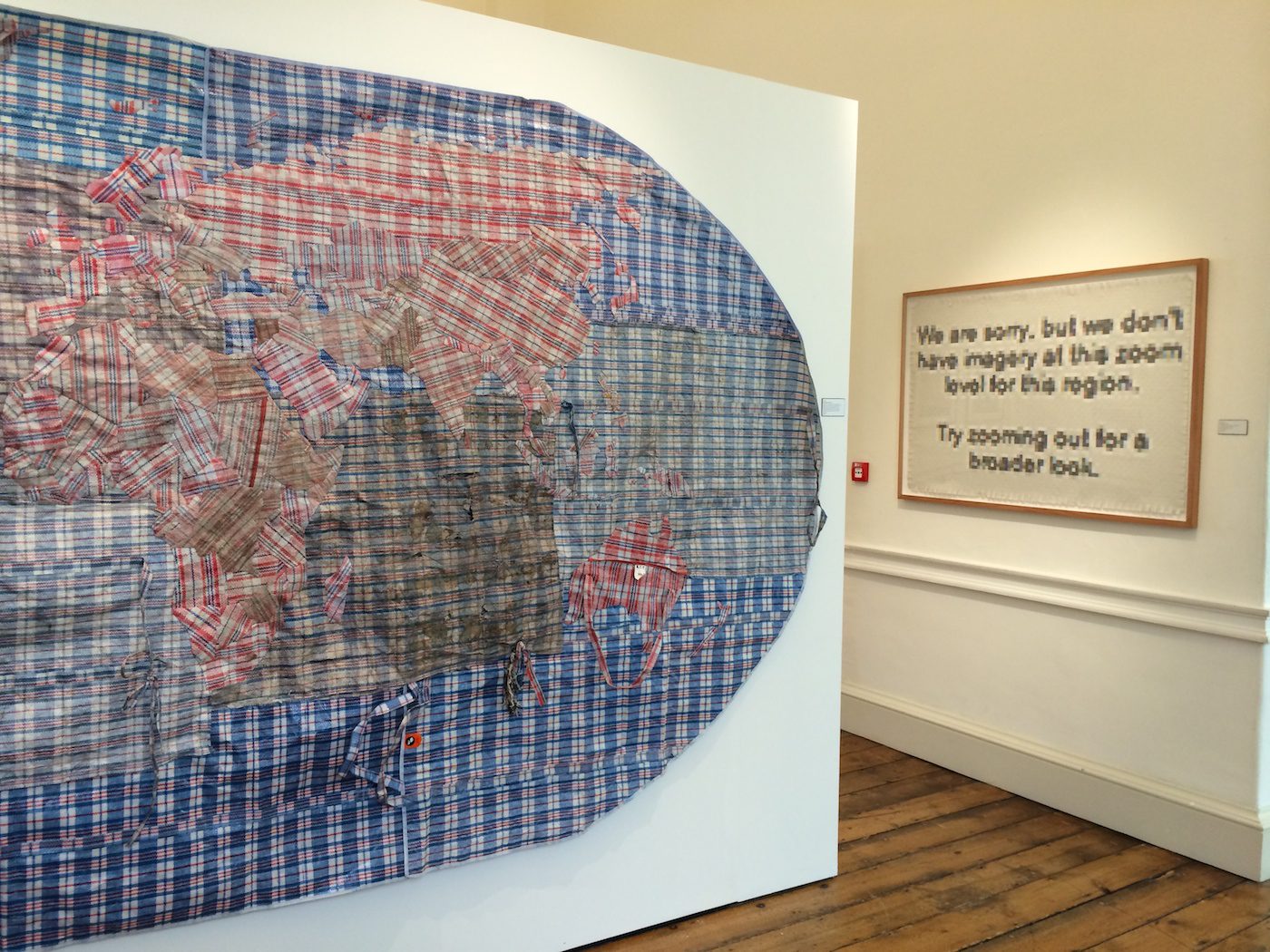

Whatiftheworld will be exhibiting four of their artists, along with another three on a rotating basis. The aim of their exhibition will be to showcase diversity, artists from different countries and race groups. Racial stereotypes are common on the African Continent. Whatiftheworld attempts to break down those boundaries, and instead exhibit the art for the dialogues they create. Dan Halter, a white Zimbabwean now living in South Africa, works with ideas of dislocated identity through the medium of “craft imagery”. Working with stone sculpture, weaving, sewing, and other forms of local visual strategies in a conceptual way, he breaks down boundaries between curiosity/craft objects and “fine art”. Halter intertwines narratives embedded with the fabric of “African” history, such as abuse of power, colonialism, the idea of nation states, and Halter’s own history, as a man stuck between what it means to be a European and African.

Athi-Patra Ruga is from Umtata, South Africa, where Nelson Mandela was born and home to one of the only Black Universities open during apartheid. His history is visible in his work. He explores the idea of maps, border-zones between all varieties of visual art. As is the case across most of the African Continent, the modern conflicts are due to arbitrary boundaries placed by colonial powers, causing forced migration and mass exodus. Ruga works with this idea of disenfranchisement created by cultural/political mechanisms of government and nationalism. In response, Ruga creates his own, almost utopian, republic; one where a persons cultural identity is not constrained by geographical boundaries or ancestry. He is changing what people think when they think of Africa. Instead of death, destruction, the dark continent, his work allows people to engage with art and Africa from a slightly different perspective. Although his issues are multifaceted, his aesthetic remains colorful and exuberant as he draws inspiration from camp culture and the fashion world.

John Murray is an older white South African painter, whose works provides a nice contrast to many of the other artists Whatiftheworld will be exhibiting. His work is predominantly abstract with a very modernist feel. He moves between representational and non-representation forms creating a dialog between the known and unknown. The Nigerian photographer, Lakin Ogunbanwo, is 27 years old and lives in Lagos. Ogunbanwo combines the aesthetic of fashion photography and classical portraiture to challenge such societal notions with strong erotic and sensual undertones. His photographs are predominantly of young Lagosian males draped in shadows or highlighted with blocks of deep color, reminiscent of African studio photography from the mid-twentieth century.

Cameron Platter will be part of Whatiftheworld’s rotating exhibition. He is one of the gallery’s intentionally prolific artists. He works with rudimentary raw tools to create woven textiles and carvings. His materials, recognizably representative of an African sensibility, give his work a sense of naivety, but his themes are very complex dealing with cultural divides between the rich and poor, consumerism and humanity, our desires and place in the world.

Interview conducted by Emma Wingfield.